‘Shell’

‘Shell’, calcium carbonate from dissolved seashells and seawater from the mouth of the Exe Estuary, 2021 Photo: Rhodri Cooper Photography

Shells are a part of our everyday lives, from the ground we walk on to the food we eat.

Inspired by 200 year-old books in the Devon and Exeter Institution, I’ve been looking at the science and symbolism of shells and shellfish: edible mussels in the River Exe, ‘shell money’ in the slave trade, their part in the ecosystem and the effects of climate change on their ability to grow and reproduce.

Invited to explore the collections in the DEI, I found a book that intrigued me: ‘A Conchological Dictionary of the British Islands by William Turton M.D, assisted by his daughter’. Gratified that she at least got a mention, but slightly miffed that she isn’t named, I looked further into books on shells and shellfish and marine biology of the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries.

Often women played a huge part in the scientific and artistic research:

Testacea Britannica (1803): Illustrations by Elizabeth D’Orville, text by George Montagu.

The year he died, 1815, Montagu gave copies Testacea Britannica to the science collection at the new Devon and Exeter Institution (DEI) and the shells to his son, Henry D’Orville, who subsequently gave them to the Royal Albert Memorial Museum (RAMM) in Exeter.

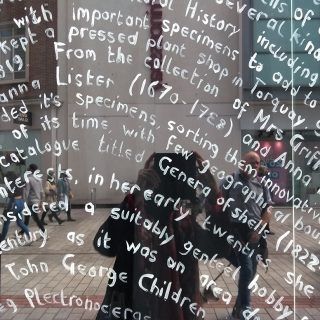

‘Historiae Conchyliorum’ 1685: Engravings by Susanna and Anna Lister, text by Martin Lister. All the more extraordinary since Susanna and Anna (Martin’s daughters) were teenagers at the time they did this work, and did all of the visual research, etching and printing of the plates themselves.

English translation of ‘Lamarck’s Genera of Shells’, c1820: illustrations by Anna Atkins, text by John George Children. Anna is better known for her cyanotype work on marine algae, but was also an accomplished scientific illustrator.

Shells enter every part of our lives.

We talk of ‘shell money’, which often refers to Monetaria moneta or the money cowrie, historically used as currency in many parts of the world.

During the Slave Trade, these were brought from the Indian Ocean to the UK as ballast in ships, then taken to West Africa to be traded in exchange for enslaved people. Many people and businesses in Exeter were deeply involved in this trade.

Shells have traditionally been used in ceremonies and as fertility charms in pregnancy and childbirth.

Shellfish such as scallops, clams, oysters and mussels are a huge part of our diets and a global industry. Shell middens often form small islands or landbanks where our ancestors ate them in their thousands and discarded the empty shells. Shellfish are often filter feeders, extracting organic matter from the sea in which they live and recycling nutrients that enter waterways from human and agricultural sources. They provide an enormous service to us, but we have to remember that all the pollution (plastic, fertilizers etc) that is in our water will end up inside the animals.

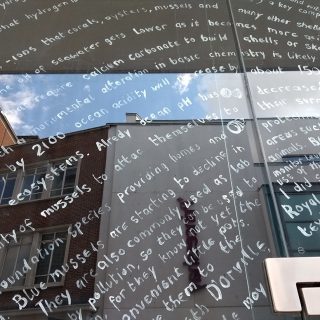

Our oceans are warming and becoming more acidic and acid breaks down the calcium carbonate in shells. Using shells from the Exe Estuary and lemon juice, I’ve accelerated and exaggerated this process and produced my own chalk.

The text is taken from various books and articles about shells.

‘Shell’ is a testament to nature, to science and scientists (especially forgotten ones), to the slow accretion of knowledge that has built our understanding of the world and to the fragility of life and our ecosystem, which we need to nurture and to care for.

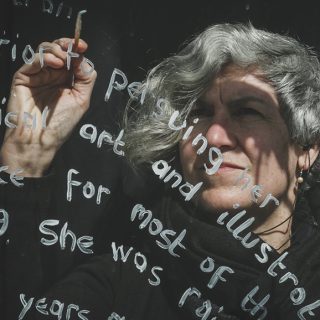

I made the working live in situ in the old Carphone Warehouse off Exeter High Street, opposite River Island (appropriately) on 10th and 11th April, assisted by the music of Al Swainger, who composed two pieces especially for this as part of his Pointless Beauty project.

‘Shell’ will remain until 31st May.

Led by Exeter Culture, it is funded by the Liveable Exeter programme, managed by Exeter City Council, and the Next Chapter project at the Devon and Exeter Institution, funded by the National Heritage Lottery Fund. Huge thanks also to Princesshay, Exeter Phoenix, Maketank, Topos, Al Swainger, Rhodri Cooper photography, Dr Ceri Lewis and everyone else who helped.

‘Shell’, calcium carbonate made from dissolved seashells and seawater, both from the mouth of the Exe Estuary, Naomi Hart, 2021.