Reading Water: life and death

31 December 2020

31st December

I tend to try and focus on the beautiful aspects of the river, especially as an escape from daily worries, and the sight of the resident kingfisher, with its blue-green-gold flash, is always cheering, but there are constant signs of our neglect of nature around, too.

Valerie Bloom’s wonderful rhythmic poem ‘I asked the river’ pulls us in to a bubbly conversation with a river, only to end with a damning rebuke for how we should treat the environment better. Walks along the city section of the Exe certainly features rather too many traffic cones and shopping trolleys, not to mention the invisible microplastics that are omnipresent in our ecosystems now.

‘Why don’t you fight for your life?’ I asked,

‘You only foam and seethe.’

‘My lungs are clogged,’ the river moaned,

‘And I can hardly breathe.’

‘Perhaps a rest,’ I told the river,

‘Would help to clear your head.’

‘I cannot rest,’ the river said,

‘There’s garbage in my bed.’

(‘I asked the River’ – Valerie Bloom)

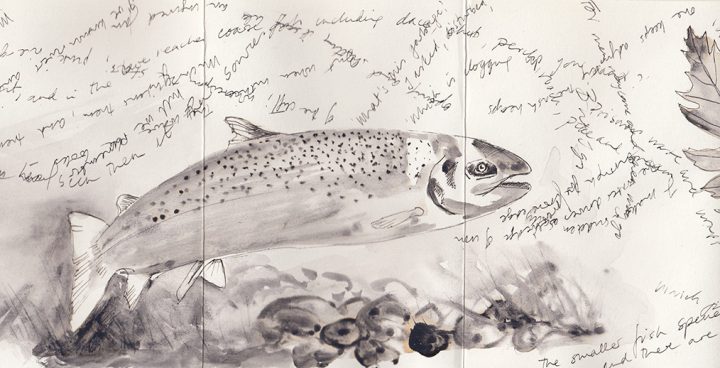

I saw tiny minnows in the flood relief channel, skittering in a little cloud when I moved or the light changed. On occasion I have been lucky enough to look down on the water from one of the footbridges and see salmon leaping and think of the tremendous journeys they make from river to sea and back again to spawn. Walking along the shores of the Exe, I have found small private gated areas ‘Private fishing’ and signs telling me in several languages that I am not allowed to fish. I’ve never quite understood hobby fishing, as opposed to fishing to eat, but probably it’s like my need to take my sketchbook and just sit in a lovely place for hours.

Apparently the Exe has ‘wild brown trout , and in the lower reaches coarse fish including dace, chub, perch, roach, pike and bream and some grayling, the average size being 8–10 ounces (230–280 g). There is a run of Atlantic salmon and a sparse run of sea trout.’

Christian Schubart tells a tale of watching a fisherman in a battle of wits with a trout. The poem was perhaps made famous by being set to music by Franz Shubert:

‘So lang dem Wasser Helle,

So dacht ich, nicht gebricht,

So fängt er die Forelle

Mit seiner Angel nicht.’

(As long as the water

is clear, I thought,

he won’t catch the trout

with his rod.)

(‘Die Forelle’ (The Trout) – Christian Schubart)

Translations are clunky, and can very rarely retain all the multiple meanings and grace of the original. Languages contain whole cultures and different ways of thinking, and I am reminded how wonderful it is to have people from so many cultures who call the Exe Estuary their home.

‘My hometown, like the stars just blinking on,

Is somewhere on the other side of a wide, wide river’

Reading Water: ships, wars, trade, slaves

7 December 2020

6 December 2020

Behind the wall at Riversmeet, the sun warm on my face, protected from the wind, I print the mud, we watch a heron and an egret, closer than I have ever seen them, stock still at the water’s edge, then stepping, purposefully to gain a new perspective. We hunt for ancient treasure: bottle, military buttons, pottery from ages past.

Topsham was once the second largest port after London and an important shipbuilding town.

Standing in the warm sunshine at Riversmeet House, where the Exe meets the Clyst, staring out to the sea in the distance; in Emily Dickinson’s words in ‘My river runs to thee’, ‘Say, sea, Take me!’ I feel the real desire to swim, but this isn’t a good place.

Making our way upriver along the foreshore, past the Dutch houses and former shipyards, I think of one of my favourite childhood poems, so wonderful to recite:

‘Quinquireme of Ninevah from distant Ophir,

Rowing home to haven in sunny Palestine,

With a cargo of ivory

And apes and peacocks,

Sandalwood, cedarwood and sweet white wine.’

Each verse is steadily less romantic and more grubbily realistic, but it’s incredibly visually rich, and has such wonderful rhythm that I never tire of it.

Riversmeet was built by one of the major shipbuilders and I stand and imagine the great wooden bombships heading in the once-deep channel to the sea. One of these ships was present at the battle of Fort McHenry in America during the 1812-1815 war, and a poem was written about the battle. That poem became the American National Anthem, linking the small town of Topsham with one of the great events of American history.

‘And the rocket’s red glare, the bombs bursting in air,

Gave proof through the night that our flag was still there;

O say does that star-spangled banner yet wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave?’

(‘Star-spangled Banner’ – Francis Scott Key)

The shipbuilder’s family (Davy) was also deeply involved in the slave trade, as were many families in Devon, and we are reminded how rivers, tides and ocean currents connect us with the world and how they have been integral in how trade routes developed. In ‘The Negro speaks of Rivers’, Langston Hughes names rivers which embody human history, particularly Black History.

I once kayaked downriver into a side channel, overgrown with willows and reeds, it felt like Florida swampland, and we like intrepid explorers. On those days the river is all rivers and all stories.

‘I’ve know rivers ancient as the world and older than the flow of human blood in human veins.’

Reading Water: fragility

2 December 2020

2 December 2020

2 December 2020

I headed upstream a little, towards the railway. Here the river and flood defence channel swing round the city in an arc. St Thomas traditionally used to flood every few decades and still comes perilously close sometimes. New walls are being built to contain the floodwaters. In the trees between the river and the flood channel I find tents, battered by recent storms, the childish colours are jarring in the dark woods. This was someone’s home, however fragile it appears. Now ripped and waterlogged, someone has yet again had to move on.

‘You go because hope, need and escape

are names for the same god. You go because life

is sweet, life is cheap, life is flux

and you can’t take it with you. You go because you’re alive,

because you’re dying, maybe dead already. You go because you must.’

(‘Time to Fly’ (from the Mara Crossing) – Ruth Padel )

Up by the railway bridge, deep in the undergrowth, I find a small pile of glass bottles someone has dug out of the earth. Often in the past bottles were thrown into dumps, and building work, like the railway, or the flood defence wall, bring them up into the light again. Most are broken, but some are whole, from all different eras. They would have contained medicine, food, drinks, superseded nowadays by plastic and aluminium cans.

‘Into the stream I flung

A bottle of clear glass

That twirled and tossed and spun

In the water’s race

Flashing the morning sun.’

(‘The River’ – Kathleen Jessie Raine)

The river is silvery, calm, running like glass down to the weir.