Convex Seascape Survey

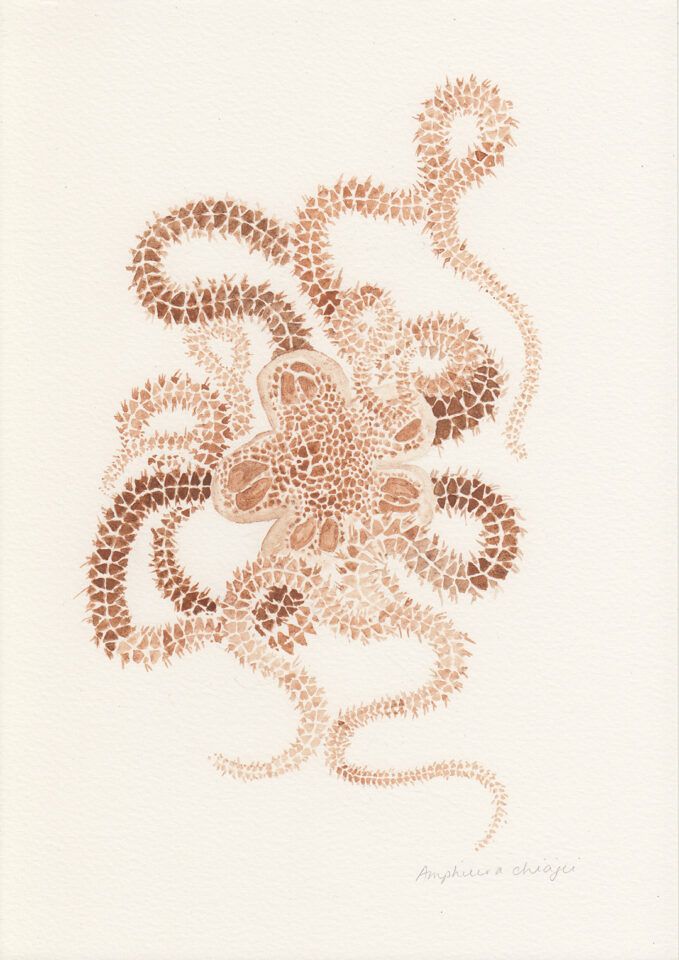

Amphiura chiajei:

A small brittlestar with very long arms, which lives buried in muddy sand. The disc may be up to 11mm in diameter with upper and underside surfaces covered in small smooth scales. Each arm segment has between 4-6 short spines on each side, none flattened or widened at the tip, and two large tentacle scales. Colour in life reddish or greyish-brown, often somewhat mottled.

It is found in the northeastern Atlantic Ocean and adjoining seas to a depth of 1000 metres. It digs itself into the soft sediment of the seabed and raises its arms into the water above to suspension feed on plankton.

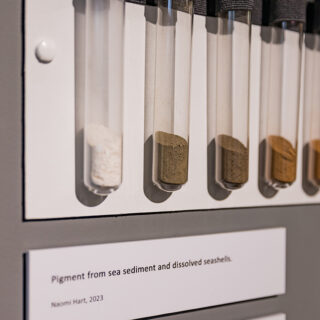

Last year, I spent two weeks embedded with scientists from the Convex Seascape Survey during their field research at the Field Studies Centre, Millport on the Isle of Cumbrae, Scotland. I accompanied them at every stage, from mud grabs in a research vessel at sea, to setting up and monitoring the benthic invertebrates back in the lab, creating field sketches as they worked. While scientists were observing the invertebrates and busy taking thousands of measurements, I took some of this sediment and created various pigments by heating it to different temperatures in a furnace. My own experiments with temperature has led to a unique colour range completely specific to the waters around the Isle of Cumbrae, so with a nod to traditional earth colours like ‘Raw Umber’ and ‘Burnt Umber’, I have named the pigments ‘Raw Cumbrae’ and ‘Burnt Cumbrae’. To extend the palette, I have also experimented with white chalk made from dissolving sea-shells in acid/lemon juice – mimicking ocean acidification as the oceans warm – and bone black, made from sea-sculpted bones washed up on the shores of Cumbrae.

With assistance from these world-leading scientists, I studied the invertebrates under a microscope and have created ‘portraits’ of them from the very mud in which they live. Hugely magnified, these creatures may seem like aliens from another world, but they are found in our oceans, creating tunnels and burrows in the mud and drawing down nutrients and carbon in the world’s largest carbon sink. Through these illustrations, I hope to raise awareness of these incredible creatures and the vitally important habitat they create. The colours themselves demonstrate the capacity of the sediment to hold nutrients and carbon: Raw Cumbrae is a mid-greybrown; as it is heated, the organic matter begins to burn and darken, and reveal the carbon stored within. Further heating burns off this carbon entirely to reveal the iron-rich red sandstone of the underlying geology.

The delicate, paper images are deliberately displayed unframed, echoing the fragility and vulnerability of the ecosystem. The hand-made, sustainably-created materials not only minimise the carbon footprint of the artwork, but demonstrate the possibilities we have of making active choices in our lives to protect and conserve the ocean.

Turritellinella tricarinata

The Augur shell is a tall, slender, sharply pointed cone. There may be as many as 20 whorls, each bearing spiral ridges and grooves. The shell is brownish- yellow to white in colour and often with a lilac tinge on the base, and grows up to 3 cm in length and 1 cm wide. The shell aperture is small and rather square in shape. The operculum is edged with pinnate bristles. The foot of the snail is small, the flesh buff with dark spots and streaks and there are white markings on the tentacles, siphon and foot.

Common around Britain and Ireland, found in the Mediterranean, and from Norway to North Africa.

Abundant on muddy sediments in shallow water, more or less buried but maintaining contact with the water. This species is slow moving and sits on the seabed filtering seawater for particles of food. It may be gregarious, occurring in large numbers.

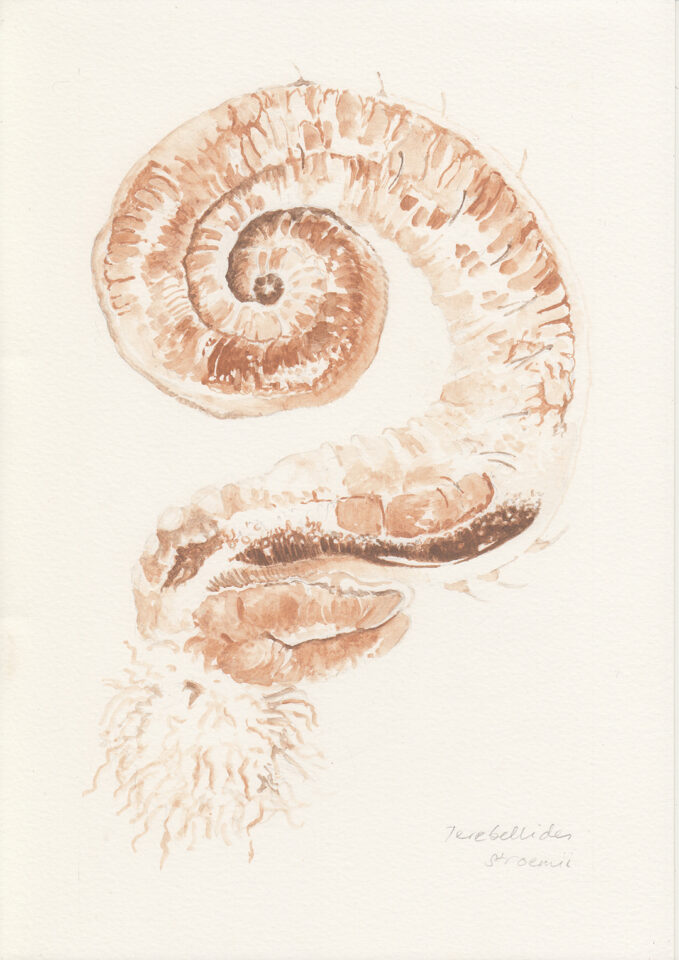

Terebellides stroemii

A species of segmented worms in the family Trichobranchidae, and known as the spaghetti worm. They are downward conveyors, meaning they are head-up feeders, which actively select and ingest particles at the surface and egest these as faeces in deeper sediment. Individuals can grow to 10cm. They have parental care and are swimmers.

Priapulus caudatus

Known as the cactus worm, it is a marine invertebrate belonging to the phylum Priapulida. It is a cylindrical, unsegmented worm which burrows in soft sediment on the seabed.

Priapulus caudatus grows to a length of 15 cm (6 in). The body is divided into two distinct regions; at the front is the introvert, ridged longitudinally and heavily armed with rows of spines. The mouth is at its tip and is surrounded by seven rows, each with five teeth. The introvert is retractable into the trunk, a longer and broader region with transverse, ring-like markings. It is terminated on the ventral side by a much-branched, tail-like appendage. The whole animal is a pinkish-brown colour and it feeds on other marine worms.

Glycera alba:

Bloodworms are a creamy pink colour, as their pale skin allows their red body fluids that contain haemoglobin to show through – the origin of the name ‘bloodworm’. At the ‘head’, they have four small antennae and small fleshy projections called parapodia running down their bodies.

Growing up to 35cm in length, they are carnivorous and feed by extending a large proboscis that bears four hollow jaws. These jaws are connected to glands that supply venom, which they use to kill their prey, and their bite is painful even to a human. They are preyed on by other worms, bottom-feeding fish, crustacea, and gulls.

These animals are unique in that they contain a lot of copper without being poisoned. Their jaws are unusually strong since they too contain the metal in the form of a copper-based chloride biomineral, known as atacamite, in crystalline form. It is theorised that this copper is used as a catalyst for its venomous bite.

Cerastoderma edule:

The common cockle is a species of edible saltwater clam, a marine bivalve mollusc in the family Cardiidae, the cockles, and typically feeds on phytoplankton, zooplankton and organic particulate matter. It tolerates a wide range of salinity and wide range of temperatures, which helps to explain its very extensive range. It has a first spawning period in early summer, and a second one in the fall. Lifespan is typically five to six years.

The common cockle is one of the most abundant species of molluscs in tidal flats located in the bays and estuaries of Europe. It plays a major role as a source of food for crustaceans, fish, and wading birds, as well as humans. These animals were probably a significant food source in hunter-gatherer societies of prehistoric Europe, and shell-imprints have been found in clay remains, showing they were used for art.

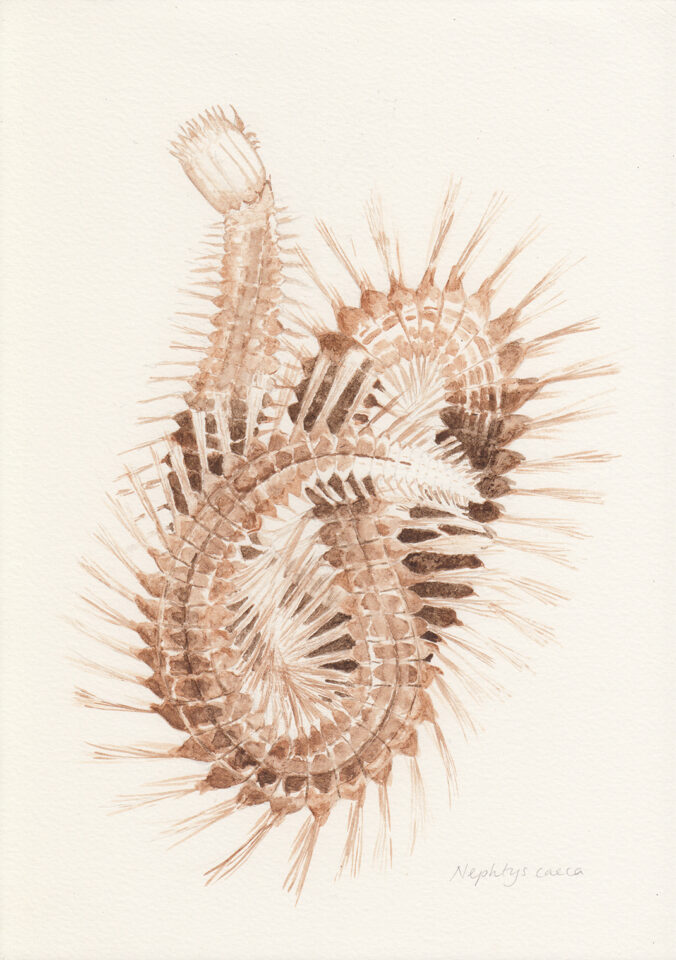

Nephtys caeca:

Called catworms, because if you look at their head under a microscope, their square head and antennae look a bit like a cat’s head. Their antennae are more like cat’s sensory whiskers than ears, allowing them to feel their way through mud as they crawl and burrow. Nephtys caeca can live a surprisingly long time for a worm, prowling the mud for about seven years. We know because they lay down growth rings on their teeth (similar to tree rings) that can be reliably used to age individual worms.

They have a muscular feeding appendage, called a proboscis, that is eversible, meaning it can turn inside out and shoot out of their mouths. Once prey are gripped in their powerful jaws, they pull the proboscis – and the meal – back in.

Arenicola defodiens:

A lugworm lives in a U-shaped burrow in sand – defodiens is derived from Latin defodio ‘to dig deep’ or ‘dig up’ and refers to the depth of the black lug burrow. The U is made of an L-shaped gallery lined with mucus, from the toe of which a vertical unlined headshaft runs up to the surface. At the surface the head shaft is marked by a small saucer-shaped depression. The tail shaft is marked by a highly coiled cast of sand.

Once it burrows into the sand a lugworm seldom leaves it. It can stay there for weeks on end, sometimes changing its position slightly in the sand. It may leave the burrow completely and re-enter the sand, making a fresh burrow for breeding, but for 2 days in early October there is a mass breeding event. This is when all the lugworms liberate their ova and sperms into the water above, and there the ova are fertilized. The ova are enclosed in tongue-shaped masses of jelly about 20cm long, 8cm wide and 2.5cm thick. Each mass is anchored at one end. The larvae hatching from the eggs feed on the jelly and eventually break out when they have grown to a dozen segments and are beginning to resemble their parents. They burrow into the sand, usually higher up the beach than the adults, and gradually move down the beach as they get older.

Lugworms feed on organic material such as micro-organisms and detritus present in the sediment. They ingest the sediment while in the burrow, leaving a depression on the surface sand. Once the sediment is stripped of its useful organic content it is expelled, producing the characteristic worm cast.

They bioturbate (re-work, re-oxygenate) the sand and serve as a food source for a wide variety of other animals such as flatfish and birds. Lugworms also have a clever way to avoid being eaten — the part of them which is usually exposed to predation – the tail – can be regrown if lost, like some lizards.

Paraleptopentacta elongata:

A species of sea cucumber in the family Cucumariidae. It is found in the North-east Atlantic Ocean and parts of the Mediterranean Sea. It occupies a burrow in the seabed, from which its anterior and posterior ends project.

It has a U-shaped, or sometimes S-shaped body, reaching a maximum length of about 10 cm. The dorsal surface is covered with darker brown or grey conical projections. In small specimens, the ventral surface bears five longitudinal rows of tube feet, and in larger specimens, it bears five double rows. The cuticle is leathery, stiffened by numerous smooth ossicles, small irregular perforated plates, which form part of the body wall. The mouth, at the anterior end, is surrounded by a ring of tentacles, eight being large and much-branched, with the two on the ventral side being short and forked.

This sea cucumber can hibernate in the winter.

Echinocardium cordatum:

A heart-shaped sea urchin in the family Loveniidae. It is found in sub-tidal regions in temperate seas throughout the world and lives buried in the sandy sea floor to a depth of 10cm to 15cm. Also known as the common heart urchin or the sea potato, it can grow to 6cm to 9cm in length and is clothed in a dense mat of furrowed yellowish spines, which grow from tubercles and mostly point backwards. During life, the spines trap air which helps prevent asphyxiation for the buried urchin.

It makes a respiratory channel leading to the surface and two sanitary channels behind itself, all lined by a mucus secretion. The location of burrows can be recognised by a conical depression on the surface in which detritus collects. This organic debris is used by the buried animal as food and is passed down by means of the long tube feet.

It is reported from temperate seas in the North Atlantic Ocean, the west Pacific Ocean, around Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and the Gulf of California at depths of down to 230 metres. The lifespan of the sea potato is thought to be ten or more years.

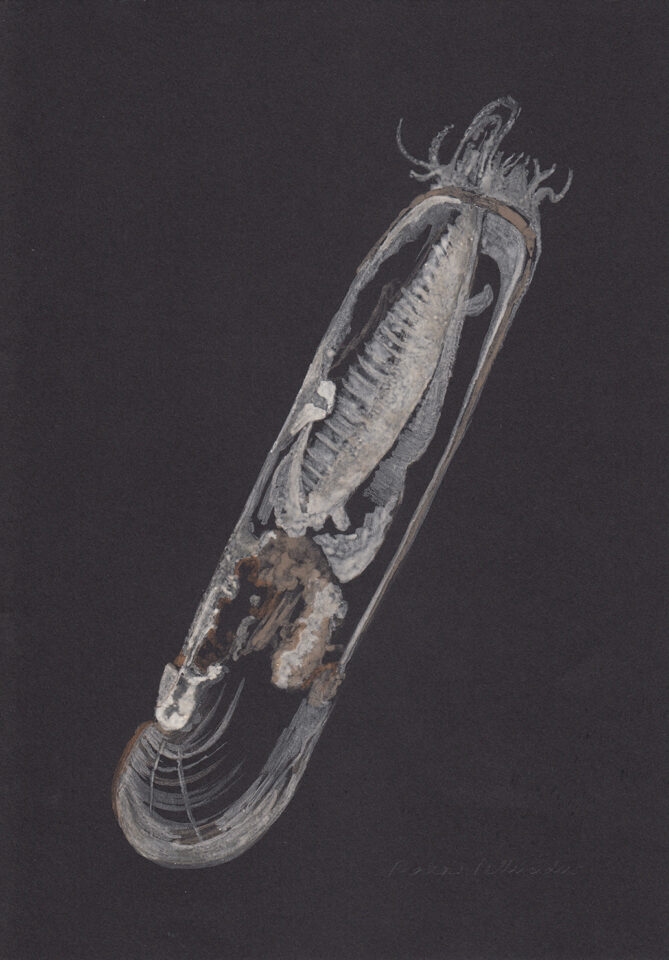

Phaxas pellucidus

A slender razor shell up to 4 cm long. The shell can be thin and brittle and coloured white or cream, sometimes with dark markings. The outermost, relatively thin layer of shell (periostracum) is a glossy light yellow-brown or olive layer. Where the shell is joined the margin is almost straight, whereas the other edge is curved giving the shell a pod shape. The anterior end is rounded and the posterior end slightly truncate.

Common off all British coasts and from Norway south to North-west Africa and the Mediterranean. It is a filter feeder and extends its siphons to the surface to circulate water through its mantle where it extracts food fragments.

(Information on the invertebrates comes from the World Register of Marine Species (WORMS), Marine Life Information Network (MarLIN), Marine Bio Conservation Society, Encyclopedia of Life, Wikipedia and Dr Adam Porter)