Collage-n

17 October 2024

Collage-n is the result of some brainstorming with text and images, helping me frame my thinking around ‘What is cultured meat?’ for a public engagement project with researchers (sociology, law and biochemistry) from The University of Birmingham, The University of Cambridge, University College London and the University of Basel.

These images led me eventually to make ‘Mana’, who toured Barnstaple in September 2024, encouraging and eliciting conversations from the public about their hopes, fears and thoughts on lab-grown meat.

Mana

2 October 2024

Mana was made to represent the many and conflicting feelings and ideas surrounding ‘cultured’ or ‘lab-grown’ meat. Mana toured Barnstaple as part of a public engagement project with researchers (law, biochemistry and sociology) from the University of Birmingham, University College London, the University of Basel and the University of Cambridge, and the project was funded by The Royal Society.

- Mana (food), archaic name for manna, an edible substance mentioned in the Bible and Quran

- Mana (Oceanian cultures), the spiritual life force energy or healing power that permeates the universe in Melanesian and Polynesian mythology

- Mana (Mandaeism), a term roughly equivalent to the philosophical concept of ‘nous’

- Māna, a Buddhist term for ‘pride’, ‘arrogance’, or ‘conceit

- Mana (Finnish mythology), or Tuonela, the realm of the dead or the underworld

Mana was created or transformed from man-made materials. The coat is a butcher’s coat or lab coat, worn by a scientist. One arm has been replaced by a matrix of wire, and on it grow flowers, symbol of nature, but all of them fake.

Mana‘s head is half head, half skull, of some beast like a cow or a goat, a deity with horns reminiscent of Hathor, the Egyptian goddess or a Hindu sacred cow – something considered immune to question or criticism. It is made from paper and flour, painted with casein paint – pigment bound by a milk protein, and one of the oldest forms of paint known on earth.

Meat muscle cells adorn Mana‘s coat, and flesh-like fabric bursts from the coat’s arm. Around Mana‘s neck are juicy-looking sausages, entirely made from fabric, as fake as the caul-like skirt that drapes and flows around Mana‘s legs.

Convex Seascape Survey

14 June 2024

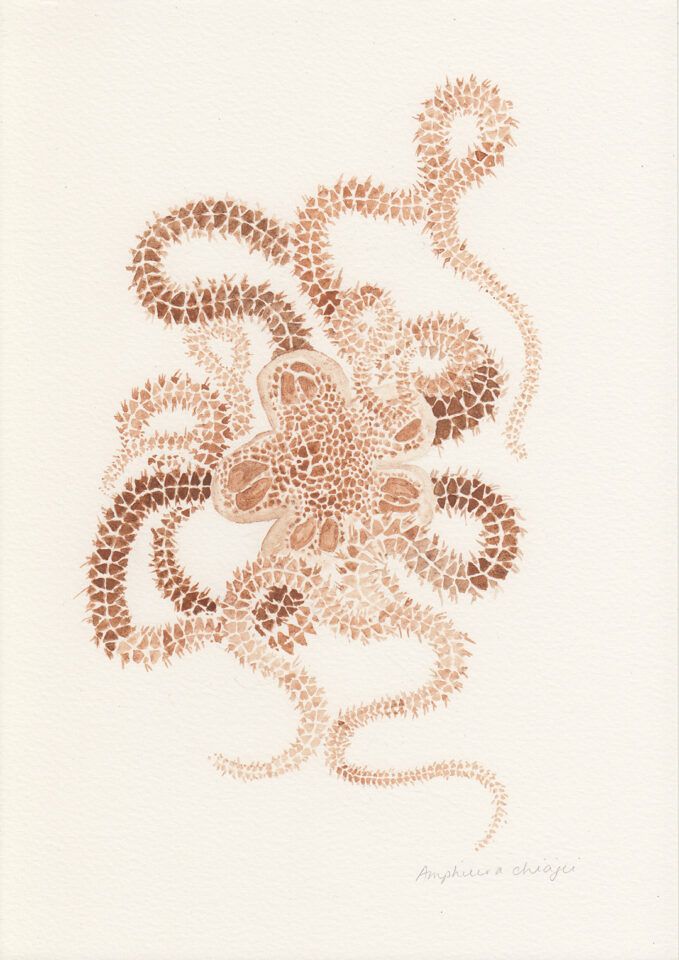

Amphiura chiajei:

A small brittlestar with very long arms, which lives buried in muddy sand. The disc may be up to 11mm in diameter with upper and underside surfaces covered in small smooth scales. Each arm segment has between 4-6 short spines on each side, none flattened or widened at the tip, and two large tentacle scales. Colour in life reddish or greyish-brown, often somewhat mottled.

It is found in the northeastern Atlantic Ocean and adjoining seas to a depth of 1000 metres. It digs itself into the soft sediment of the seabed and raises its arms into the water above to suspension feed on plankton.

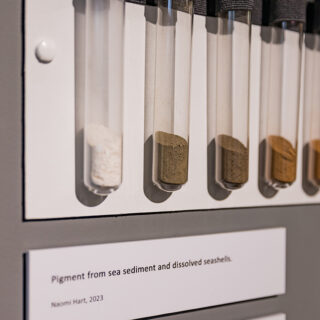

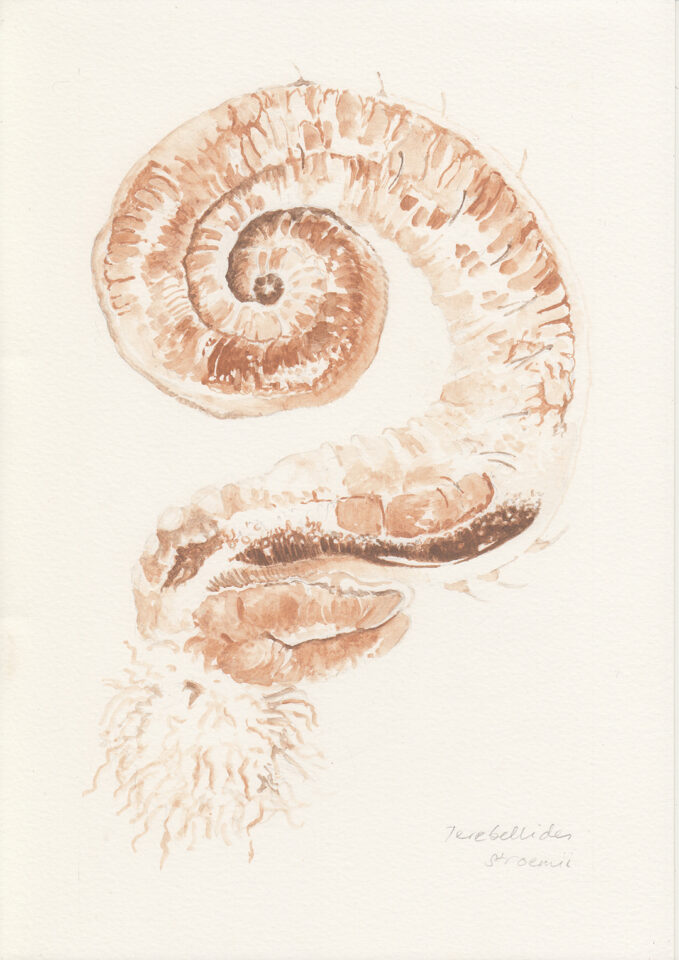

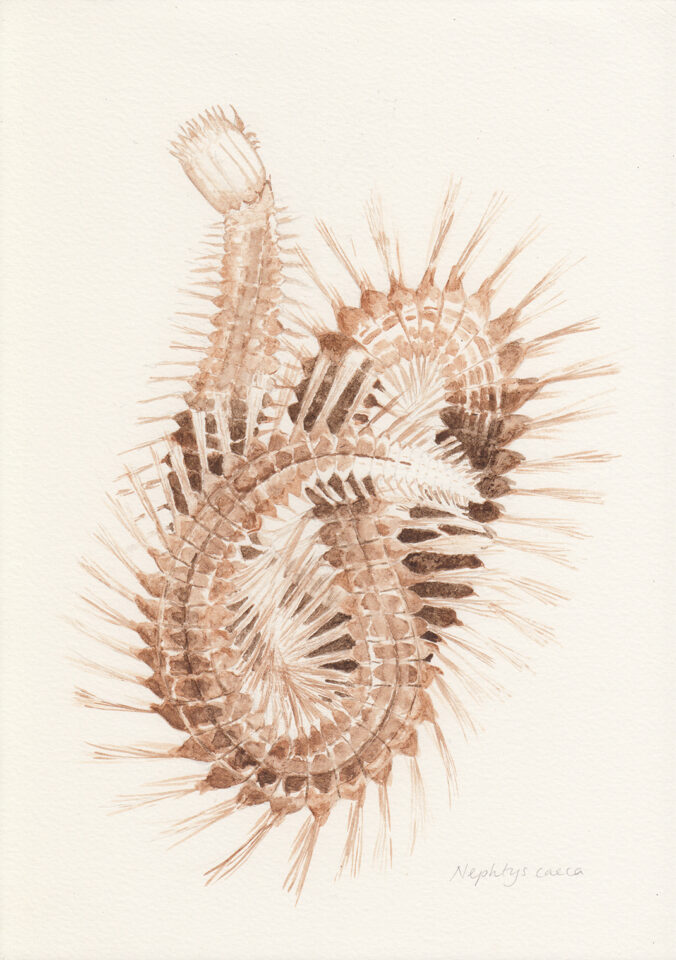

Last year, I spent two weeks embedded with scientists from the Convex Seascape Survey during their field research at the Field Studies Centre, Millport on the Isle of Cumbrae, Scotland. I accompanied them at every stage, from mud grabs in a research vessel at sea, to setting up and monitoring the benthic invertebrates back in the lab, creating field sketches as they worked. While scientists were observing the invertebrates and busy taking thousands of measurements, I took some of this sediment and created various pigments by heating it to different temperatures in a furnace. My own experiments with temperature has led to a unique colour range completely specific to the waters around the Isle of Cumbrae, so with a nod to traditional earth colours like ‘Raw Umber’ and ‘Burnt Umber’, I have named the pigments ‘Raw Cumbrae’ and ‘Burnt Cumbrae’. To extend the palette, I have also experimented with white chalk made from dissolving sea-shells in acid/lemon juice – mimicking ocean acidification as the oceans warm – and bone black, made from sea-sculpted bones washed up on the shores of Cumbrae.

With assistance from these world-leading scientists, I studied the invertebrates under a microscope and have created ‘portraits’ of them from the very mud in which they live. Hugely magnified, these creatures may seem like aliens from another world, but they are found in our oceans, creating tunnels and burrows in the mud and drawing down nutrients and carbon in the world’s largest carbon sink. Through these illustrations, I hope to raise awareness of these incredible creatures and the vitally important habitat they create. The colours themselves demonstrate the capacity of the sediment to hold nutrients and carbon: Raw Cumbrae is a mid-greybrown; as it is heated, the organic matter begins to burn and darken, and reveal the carbon stored within. Further heating burns off this carbon entirely to reveal the iron-rich red sandstone of the underlying geology.

The delicate, paper images are deliberately displayed unframed, echoing the fragility and vulnerability of the ecosystem. The hand-made, sustainably-created materials not only minimise the carbon footprint of the artwork, but demonstrate the possibilities we have of making active choices in our lives to protect and conserve the ocean.

Turritellinella tricarinata

The Augur shell is a tall, slender, sharply pointed cone. There may be as many as 20 whorls, each bearing spiral ridges and grooves. The shell is brownish- yellow to white in colour and often with a lilac tinge on the base, and grows up to 3 cm in length and 1 cm wide. The shell aperture is small and rather square in shape. The operculum is edged with pinnate bristles. The foot of the snail is small, the flesh buff with dark spots and streaks and there are white markings on the tentacles, siphon and foot.

Common around Britain and Ireland, found in the Mediterranean, and from Norway to North Africa.

Abundant on muddy sediments in shallow water, more or less buried but maintaining contact with the water. This species is slow moving and sits on the seabed filtering seawater for particles of food. It may be gregarious, occurring in large numbers.

Terebellides stroemii

A species of segmented worms in the family Trichobranchidae, and known as the spaghetti worm. They are downward conveyors, meaning they are head-up feeders, which actively select and ingest particles at the surface and egest these as faeces in deeper sediment. Individuals can grow to 10cm. They have parental care and are swimmers.

Priapulus caudatus

Known as the cactus worm, it is a marine invertebrate belonging to the phylum Priapulida. It is a cylindrical, unsegmented worm which burrows in soft sediment on the seabed.

Priapulus caudatus grows to a length of 15 cm (6 in). The body is divided into two distinct regions; at the front is the introvert, ridged longitudinally and heavily armed with rows of spines. The mouth is at its tip and is surrounded by seven rows, each with five teeth. The introvert is retractable into the trunk, a longer and broader region with transverse, ring-like markings. It is terminated on the ventral side by a much-branched, tail-like appendage. The whole animal is a pinkish-brown colour and it feeds on other marine worms.

Glycera alba:

Bloodworms are a creamy pink colour, as their pale skin allows their red body fluids that contain haemoglobin to show through – the origin of the name ‘bloodworm’. At the ‘head’, they have four small antennae and small fleshy projections called parapodia running down their bodies.

Growing up to 35cm in length, they are carnivorous and feed by extending a large proboscis that bears four hollow jaws. These jaws are connected to glands that supply venom, which they use to kill their prey, and their bite is painful even to a human. They are preyed on by other worms, bottom-feeding fish, crustacea, and gulls.

These animals are unique in that they contain a lot of copper without being poisoned. Their jaws are unusually strong since they too contain the metal in the form of a copper-based chloride biomineral, known as atacamite, in crystalline form. It is theorised that this copper is used as a catalyst for its venomous bite.

Cerastoderma edule:

The common cockle is a species of edible saltwater clam, a marine bivalve mollusc in the family Cardiidae, the cockles, and typically feeds on phytoplankton, zooplankton and organic particulate matter. It tolerates a wide range of salinity and wide range of temperatures, which helps to explain its very extensive range. It has a first spawning period in early summer, and a second one in the fall. Lifespan is typically five to six years.

The common cockle is one of the most abundant species of molluscs in tidal flats located in the bays and estuaries of Europe. It plays a major role as a source of food for crustaceans, fish, and wading birds, as well as humans. These animals were probably a significant food source in hunter-gatherer societies of prehistoric Europe, and shell-imprints have been found in clay remains, showing they were used for art.

Nephtys caeca:

Called catworms, because if you look at their head under a microscope, their square head and antennae look a bit like a cat’s head. Their antennae are more like cat’s sensory whiskers than ears, allowing them to feel their way through mud as they crawl and burrow. Nephtys caeca can live a surprisingly long time for a worm, prowling the mud for about seven years. We know because they lay down growth rings on their teeth (similar to tree rings) that can be reliably used to age individual worms.

They have a muscular feeding appendage, called a proboscis, that is eversible, meaning it can turn inside out and shoot out of their mouths. Once prey are gripped in their powerful jaws, they pull the proboscis – and the meal – back in.

Arenicola defodiens:

A lugworm lives in a U-shaped burrow in sand – defodiens is derived from Latin defodio ‘to dig deep’ or ‘dig up’ and refers to the depth of the black lug burrow. The U is made of an L-shaped gallery lined with mucus, from the toe of which a vertical unlined headshaft runs up to the surface. At the surface the head shaft is marked by a small saucer-shaped depression. The tail shaft is marked by a highly coiled cast of sand.

Once it burrows into the sand a lugworm seldom leaves it. It can stay there for weeks on end, sometimes changing its position slightly in the sand. It may leave the burrow completely and re-enter the sand, making a fresh burrow for breeding, but for 2 days in early October there is a mass breeding event. This is when all the lugworms liberate their ova and sperms into the water above, and there the ova are fertilized. The ova are enclosed in tongue-shaped masses of jelly about 20cm long, 8cm wide and 2.5cm thick. Each mass is anchored at one end. The larvae hatching from the eggs feed on the jelly and eventually break out when they have grown to a dozen segments and are beginning to resemble their parents. They burrow into the sand, usually higher up the beach than the adults, and gradually move down the beach as they get older.

Lugworms feed on organic material such as micro-organisms and detritus present in the sediment. They ingest the sediment while in the burrow, leaving a depression on the surface sand. Once the sediment is stripped of its useful organic content it is expelled, producing the characteristic worm cast.

They bioturbate (re-work, re-oxygenate) the sand and serve as a food source for a wide variety of other animals such as flatfish and birds. Lugworms also have a clever way to avoid being eaten — the part of them which is usually exposed to predation – the tail – can be regrown if lost, like some lizards.

Paraleptopentacta elongata:

A species of sea cucumber in the family Cucumariidae. It is found in the North-east Atlantic Ocean and parts of the Mediterranean Sea. It occupies a burrow in the seabed, from which its anterior and posterior ends project.

It has a U-shaped, or sometimes S-shaped body, reaching a maximum length of about 10 cm. The dorsal surface is covered with darker brown or grey conical projections. In small specimens, the ventral surface bears five longitudinal rows of tube feet, and in larger specimens, it bears five double rows. The cuticle is leathery, stiffened by numerous smooth ossicles, small irregular perforated plates, which form part of the body wall. The mouth, at the anterior end, is surrounded by a ring of tentacles, eight being large and much-branched, with the two on the ventral side being short and forked.

This sea cucumber can hibernate in the winter.

Echinocardium cordatum:

A heart-shaped sea urchin in the family Loveniidae. It is found in sub-tidal regions in temperate seas throughout the world and lives buried in the sandy sea floor to a depth of 10cm to 15cm. Also known as the common heart urchin or the sea potato, it can grow to 6cm to 9cm in length and is clothed in a dense mat of furrowed yellowish spines, which grow from tubercles and mostly point backwards. During life, the spines trap air which helps prevent asphyxiation for the buried urchin.

It makes a respiratory channel leading to the surface and two sanitary channels behind itself, all lined by a mucus secretion. The location of burrows can be recognised by a conical depression on the surface in which detritus collects. This organic debris is used by the buried animal as food and is passed down by means of the long tube feet.

It is reported from temperate seas in the North Atlantic Ocean, the west Pacific Ocean, around Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and the Gulf of California at depths of down to 230 metres. The lifespan of the sea potato is thought to be ten or more years.

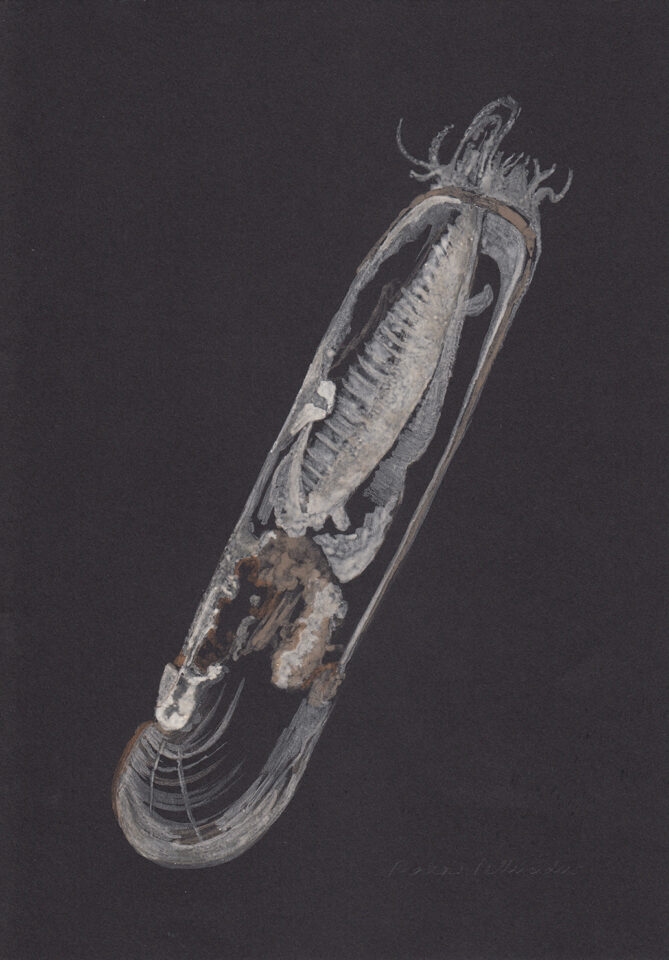

Phaxas pellucidus

A slender razor shell up to 4 cm long. The shell can be thin and brittle and coloured white or cream, sometimes with dark markings. The outermost, relatively thin layer of shell (periostracum) is a glossy light yellow-brown or olive layer. Where the shell is joined the margin is almost straight, whereas the other edge is curved giving the shell a pod shape. The anterior end is rounded and the posterior end slightly truncate.

Common off all British coasts and from Norway south to North-west Africa and the Mediterranean. It is a filter feeder and extends its siphons to the surface to circulate water through its mantle where it extracts food fragments.

(Information on the invertebrates comes from the World Register of Marine Species (WORMS), Marine Life Information Network (MarLIN), Marine Bio Conservation Society, Encyclopedia of Life, Wikipedia and Dr Adam Porter)

SeaBed

29 January 2024

SeaBed is a bedspread about the bed of the sea. It is a collaboration between scientists, refugees and artists and was made in Exeter entirely from salvaged and donated fabric.

This worm-made-of-rags depicts the ragworm, Hediste diversicolor, a common UK species of benthic worm. It lives in the mud under the sea and is an important species in marine ecology.

The border illustrations show many other species of benthic invertebrate, which are being studied by scientists from The University of Exeter as part of the Convex Seascape Survey. Their research is looking at how these benthic invertebrates cycle nutrients and store carbon, and how they may affect climate change. The Convex Seascape Survey is a five-year, pioneering global research project that will generate the critical data and insight on how to manage the ocean sustainably to maximise its carbon storage capabilities and Naomi has been working with them as artist in residence for the last year.

The embroidered pieces have been created here in Exeter by refugees and asylum-seekers, some of the people who are often most affected by climate change. People of different ages: young boys who had never sewn before, through grandmothers and mothers with their babies. They came from many different countries and spoke many languages, but with the help of images, we discussed these marine invertebrates and they embroidered them onto the fabric during several workshops.

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea argues that the areas of the ocean floor that lie totally outside national sovereignty are “the shared heritage of humanity” and is intended to guarantee that the environment is protected. Through collaboration and co-making, ‘Sea Bed’ highlights this understanding and the fragility of the undersea ecosystem. By hand forming the benthic ecosystem in sections, a human community recreates an underwater community, and we can learn more about ‘the world in our hands’. Sustainable methods and materials not only minimise the carbon footprint of the artwork, but demonstrate the possibilities we have of making active choices in our lives to protect and conserve the ocean.

SeaBed was commissioned by Exeter City Council as part of Exeter’s Cultural Compact funded by Arts Council England. Naomi is extremely grateful to Exeter Culture, Refugee Support Devon, Devon Ukrainian Association, Devon Development Education (DDE), Scrapstore, Princesshay, Maketank, St Thomas Freecycle, Exeter Quilters, ExeterMarine, The Convex Seascape Survey, all those who helped and gave advice, and all the participants:

Alla, Amina, Tehmina, Florence, Ramatu, Isatu, Yohebeth, Angel, Rabi, Gony, Hirasami, Ledion, Mudira, Jensy, Nadia, Anila, Mabel, Diana, Olya, Ross, Stiven, Ivana, Raya, Zahra, Arsen, Salgai, Suno, Ansh, Adi, Katherine, Hassim and Daniel.

For more information about the work and the research, see

https://www.youtube.com/@ConvexSeascapeSurvey_

Ragworms:

Hediste diversicolor is one of the commonest intertidal polychaetes in the UK.

Adults may reach 6-12cm in length and have between 90-120 chaetae-bearing segments, each with a pair of limbs called parapodia, which have dorsal and ventral chaetae and are used for crawling and swimming. They can regrow their bodies if broken off, as each segment contains all the main constituents of the main ‘organs’.

Ragworms spend their lives in burrows in benthic mud, taking nutrients from their surroundings in various ways. They have pair of hard pincer-like jaws which are used to grab living prey, carrion and plant material. Sometimes they leave their holes completely to hunt for food on the surface of the mud and under rocks. They produce mucous which helps gather food, and has been shown to stabilise the sediment, much like tree-roots in soil.

When they reproduce, both sexes turn green. The pigment is caused by the breakdown of their blood as they produce eggs and sperm.

When the female is ready, the couple don’t meet, the male releases his sperm outside the entrance and she sucks it inside her burrow. He then dies, and her body ruptures, releasing thousands of fertilised eggs. She will still manage to oxygenate the burrow by moving around until her larvae hatch and she, too, dies.

Hediste diversicolor is widely distributed throughout north-west Europe on the Baltic Sea, North Sea and along Atlantic coasts to the Mediterranean.

La mer

3 April 2023

My latest work, ‘La mer’, is about the intertidal zone – the shifting world between the dry and the submerged land. Twice a day, the miracle feat of walking on the bottom of the sea and then floating above the solid ground you once stood on. This is unsettling, unstable ground, negative islands in an archipelago of water. What is up, what is down? These are windows in the ocean: beneath the still surface are myriad lives, but are we looking in or looking out from under the sea? The relentless push and pull of the tides means that this space is fugitive: whenever you try to grasp a moment it vanishes; washed away like a memory, always beyond reach.

The colours may seem to offer easy connections with summer, but they also reference earth minerals brought to the surface and carved out by human hand and forces of nature: coal, rust, copper, gold. The tides can be positive, bringing new life, or destructive, eroding millennia from cliff faces in a matter of minutes. The colours of the sea have leached from the land.

There is a balance in the tides: the sanctuary of rockpools, sheltering life from heat and evaporation as the waters recede. Points of strength which hold back the floodtides become points of weakness, breached to let through a migration of water, creatures and nutrients, back and forth every few hours. The gap is light and space, and a break in the defences. Points that touch, held together by atoms until they break – the flood is released, overwhelming everything either in a rush or a slow, steady infiltration.

‘the primeval meeting place of the elements of earth and water, a place of compromise and conflict and eternal change.’

(Rachel Carson, ‘The Edge of the Sea’)

These paintings are all for sale unless marked sold. Please email me at naomi@naomi-hart.com or use the contact form if you are interested in purchasing. Thank you.

20cm x 20cm £150 +p&p

30cm x 30cm £300 +p&p

40cm x 40cm £450 +p&p

60cm x 60cm £1050 +p&p

‘Shell’

8 April 2021

‘Shell’, calcium carbonate from dissolved seashells and seawater from the mouth of the Exe Estuary, 2021 Photo: Rhodri Cooper Photography

Shells are a part of our everyday lives, from the ground we walk on to the food we eat.

Inspired by 200 year-old books in the Devon and Exeter Institution, I’ve been looking at the science and symbolism of shells and shellfish: edible mussels in the River Exe, ‘shell money’ in the slave trade, their part in the ecosystem and the effects of climate change on their ability to grow and reproduce.

Invited to explore the collections in the DEI, I found a book that intrigued me: ‘A Conchological Dictionary of the British Islands by William Turton M.D, assisted by his daughter’. Gratified that she at least got a mention, but slightly miffed that she isn’t named, I looked further into books on shells and shellfish and marine biology of the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries.

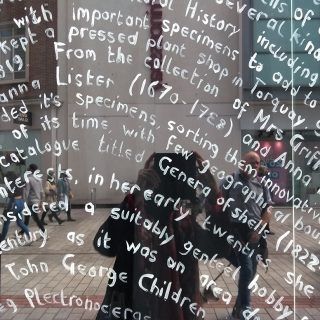

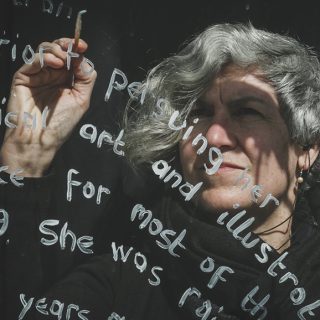

Often women played a huge part in the scientific and artistic research:

Testacea Britannica (1803): Illustrations by Elizabeth D’Orville, text by George Montagu.

The year he died, 1815, Montagu gave copies Testacea Britannica to the science collection at the new Devon and Exeter Institution (DEI) and the shells to his son, Henry D’Orville, who subsequently gave them to the Royal Albert Memorial Museum (RAMM) in Exeter.

‘Historiae Conchyliorum’ 1685: Engravings by Susanna and Anna Lister, text by Martin Lister. All the more extraordinary since Susanna and Anna (Martin’s daughters) were teenagers at the time they did this work, and did all of the visual research, etching and printing of the plates themselves.

English translation of ‘Lamarck’s Genera of Shells’, c1820: illustrations by Anna Atkins, text by John George Children. Anna is better known for her cyanotype work on marine algae, but was also an accomplished scientific illustrator.

Shells enter every part of our lives.

We talk of ‘shell money’, which often refers to Monetaria moneta or the money cowrie, historically used as currency in many parts of the world.

During the Slave Trade, these were brought from the Indian Ocean to the UK as ballast in ships, then taken to West Africa to be traded in exchange for enslaved people. Many people and businesses in Exeter were deeply involved in this trade.

Shells have traditionally been used in ceremonies and as fertility charms in pregnancy and childbirth.

Shellfish such as scallops, clams, oysters and mussels are a huge part of our diets and a global industry. Shell middens often form small islands or landbanks where our ancestors ate them in their thousands and discarded the empty shells. Shellfish are often filter feeders, extracting organic matter from the sea in which they live and recycling nutrients that enter waterways from human and agricultural sources. They provide an enormous service to us, but we have to remember that all the pollution (plastic, fertilizers etc) that is in our water will end up inside the animals.

Our oceans are warming and becoming more acidic and acid breaks down the calcium carbonate in shells. Using shells from the Exe Estuary and lemon juice, I’ve accelerated and exaggerated this process and produced my own chalk.

The text is taken from various books and articles about shells.

‘Shell’ is a testament to nature, to science and scientists (especially forgotten ones), to the slow accretion of knowledge that has built our understanding of the world and to the fragility of life and our ecosystem, which we need to nurture and to care for.

I made the working live in situ in the old Carphone Warehouse off Exeter High Street, opposite River Island (appropriately) on 10th and 11th April, assisted by the music of Al Swainger, who composed two pieces especially for this as part of his Pointless Beauty project.

‘Shell’ will remain until 31st May.

Led by Exeter Culture, it is funded by the Liveable Exeter programme, managed by Exeter City Council, and the Next Chapter project at the Devon and Exeter Institution, funded by the National Heritage Lottery Fund. Huge thanks also to Princesshay, Exeter Phoenix, Maketank, Topos, Al Swainger, Rhodri Cooper photography, Dr Ceri Lewis and everyone else who helped.

‘Shell’, calcium carbonate made from dissolved seashells and seawater, both from the mouth of the Exe Estuary, Naomi Hart, 2021.

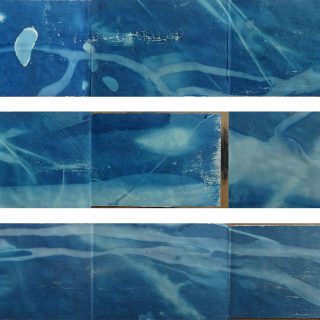

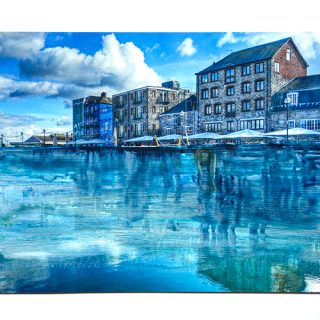

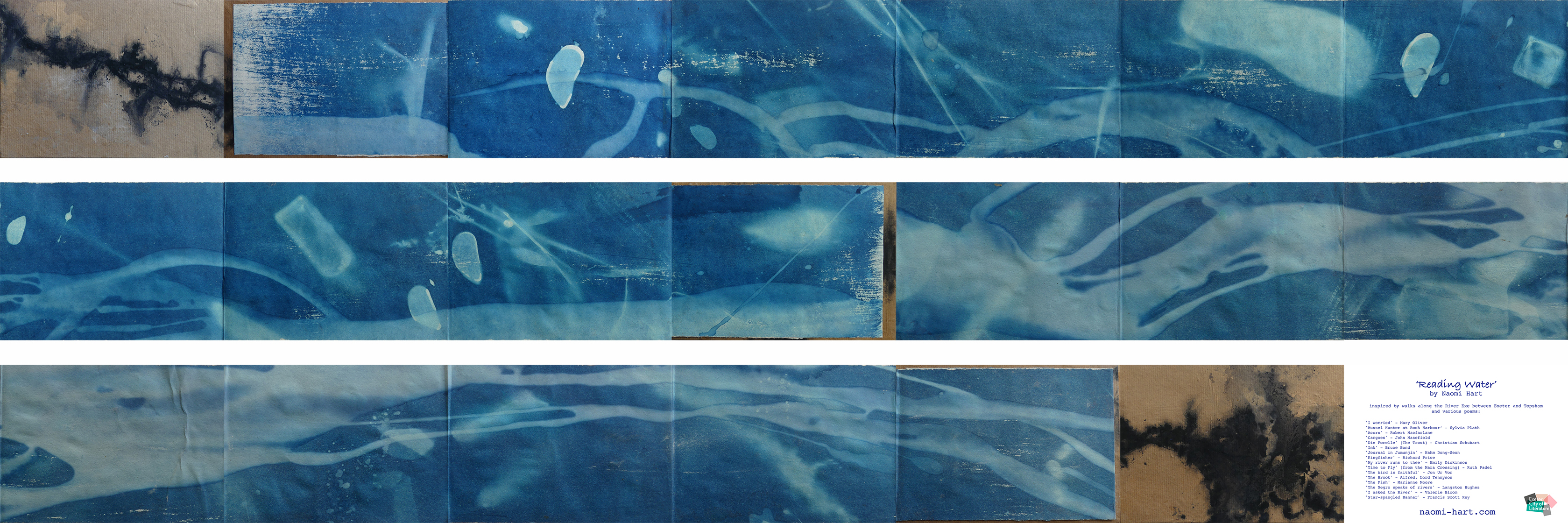

Reading Water

29 January 2021

Reading Water, mixed media, Naomi Hart, 2021

This was a lovely commission from Exeter UNESCO City of Literature and I’m very grateful to them for the opportunity to make some new work and learn more about the River Exe.

I have also been asked to create an exhibition of work for St Nicholas’ Priory, and this will form part of that. We hoped to show the work in January, but have had to postpone, so keep an eye here for details.

For this project I wanted to follow the course of the River Exe from Exeter to Riversmeet in Topsham, walking along the east bank, reading poems and texts about rivers that I feel are relevant or inspiring and collecting objects and materials to make an artist’s book. The river had other ideas, so the walks were broken and meandering, much like the river itself.

The piece is called ‘Reading Water’ – a term used by people who fish, by sailors and surfers, trying to understand what is happening on and in the water’s waves, currents and tides. The root of the name Exeter is ‘Isca’, meaning ‘water’, so this piece is both ‘reading Exeter’ and ‘reading the river’.

I invite you to read the water if you are able to walk, kayak, swim, or cycle along and around the river. Many of the poems are available online, which I invite you to read and ponder, or find your own books or poems that spark your imagination. Perhaps you want to make your own book, or write your own words about this river or another river.

The final piece is a book of cyanotype prints of water, fragments of poems and objects that I found while walking, some natural, some manufactured. Some of the poems I read are about wildlife in rivers, some are about rivers far away and remind me how we are connected to other places and times by water.

As the river water is part of a great cycle of nature, the book has been made using re-purposed paper (lining paper, wrapping paper, paper salvaged from an office fire), home-made glue (wheat flour, water), home-made oak gall ink (including oak galls, rust, wine found in an Exe Valley nature reserve, wine vinegar and river water), ascorbic acid (lemon juice), mud from the Exe, natural chalk and cyanotype using river water.

Huge thanks to clockworksatellite for help with the online book.

You can read more about the walks and the making of the book in my blog.

Poems:

Where possible, I have linked to an online source.

This poem reminds me to let go of the worries in life and look at the bigger picture. Walking along the river during lockdown has helped me do this, I get caught up in the birds, the water, the light and the sounds of the river and start to relax.

‘Mussel Hunter at Rock Harbour – Sylvia Plath

Mussels are an important industry on the Exe, and I found many shells on my walks, especially close to Topsham. This poem is so rich in imagery, and links me through mud and mussels to somewhere thousands of miles away.

‘Acorn’ – from Robert Macfarlane’s Lost Words

Many different kinds of young and ancient oaks border the river Exe, and I found lots of acorns blackened by the mud.

Hundreds of years ago, this estuary would have been busy with oak sailing ships bringing people and cargoes from far-off lands. This poem is one of my childhood favourites.

‘Die Forelle’ (The Trout) – Christian Schubart

High up in Exeter’s flood defences I saw tiny fish sheltering in the shallows. The river is home to many species of fish – it’s hard to spot them in the muddy waters, but there are plenty of fishing spots along the riverbanks.

‘Ink’ – Bruce Bond

‘Journal in Jumunjin’ – Hahm Dong-Seon

‘Time to Fly’ (from the Mara Crossing) – Ruth Padel

‘The Negro speaks of rivers’ – Langston Hughes

These poems connect with other rivers around the world, and are a wonderful reminder for me of the many different nationalities of people who call the Exe Estuary home.

‘Kingfisher’ – Richard Price (from A Spelthorne Bird List)

There is a resident kingfisher (or at least one) that I have seen several times darting between the Customs House and the flood defense channel, with its electric blue plumage flashing in the sun.

‘My river runs to thee’ – Emily Dickinson

‘The bird is faithful’ – Jon Ur Vor

‘The Brook’ – Alfred, Lord Tennyson

My father chose this poem – he has always been able to quote poems at length. He learned them when he was young, and for many years it only took a word for him to launch into a remembered poem. ‘The Brook’ is another reminder of how small we are in the great scheme of things – ‘men may come and men may go, but I go on forever.’

‘I asked the River’ – Valerie Bloom

The rhythms of this poem are wonderful – echoing the fast-flowing water – and the final words reminding us that our lives impact on nature.

‘Star-spangled Banner’ – Francis Scott Key

Topsham was once the second largest port in England after London, and hundreds of ships were built and launched there. One ship, called HMS Terror, took part in the Battle of Fort McHenry in America, during the 1812 war between the United States and the United Kingdom. ‘The Star-spangled Banner’ was written about this battle, so the River Exe is linked with one of the most important events in American history.

Into silence

15 July 2019

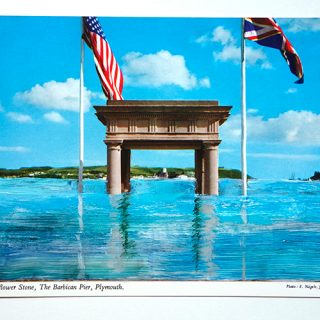

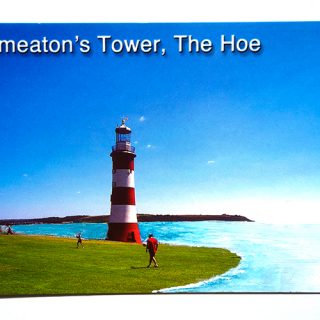

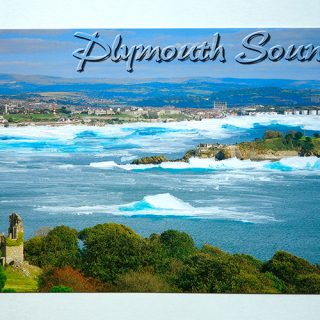

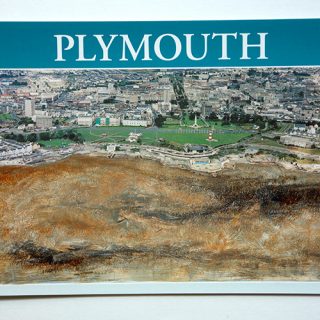

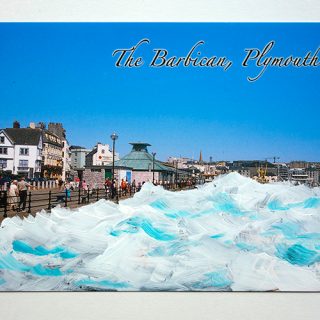

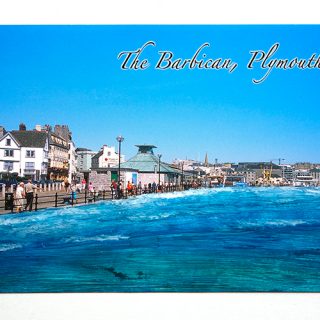

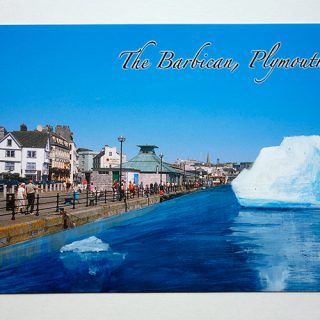

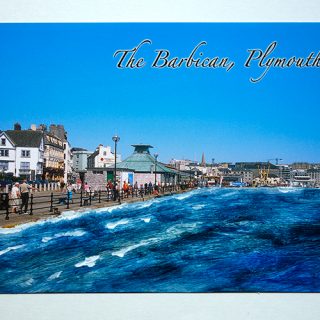

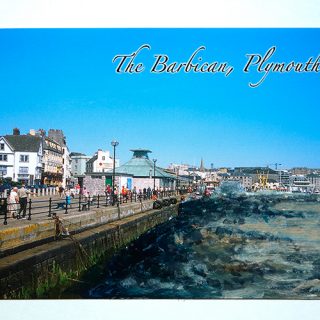

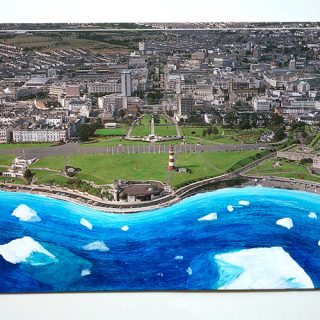

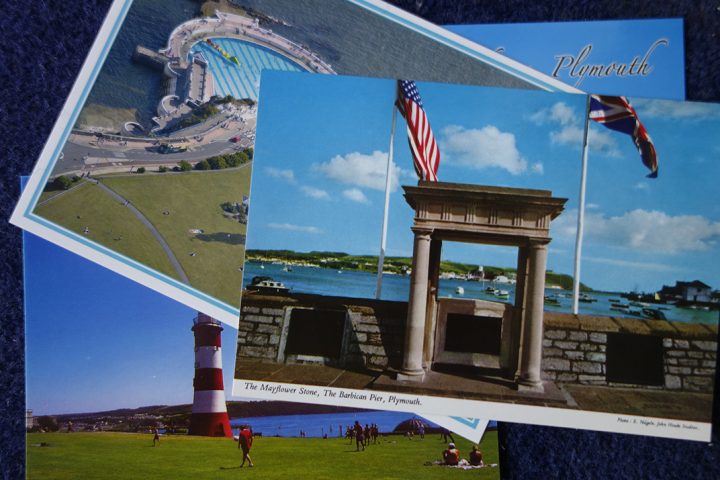

Plymouth Futures

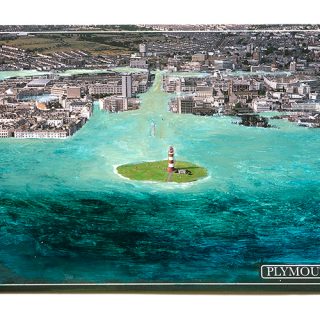

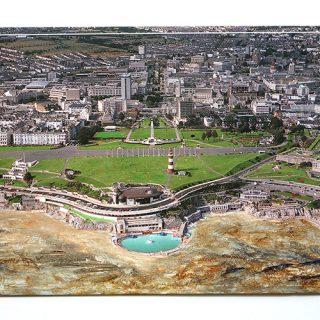

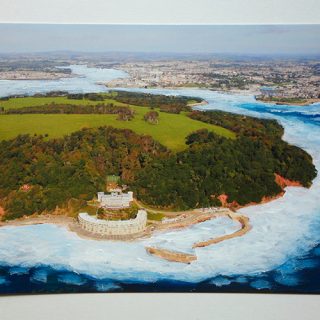

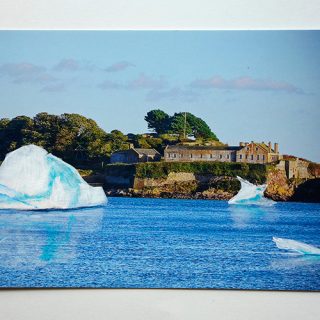

12 September 2018

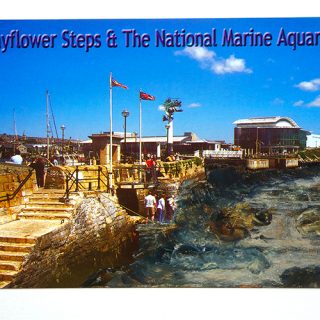

Plymouth Futures imagines how our changing climate might affect ocean levels around the city and the local coastline. There will be 101 ‘Plymouth Futurecards’ dotted around Plymouth as part of Plymouth Art Weekender and The Atlantic Project: 28 September – 21 October 2018. See how many you can find!

Share me/Keep me/Send me

#PlymouthFutures

Climate change is bringing sea level changes around the world. According to the UN, about 40% of the world’s population lives within 100 kilometres of the coast. As ice at the poles melts, sea levels rise (water expands as it warms). The salinity of the oceans will also affect currents such as the North Atlantic Drift, which currently keep Britain ice-free. For more information you could look at websites such as

carbonbrief.org/category/science/oceans